Posted May 4, 2015 by

Tags: OnCUE

After the Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of new black residents to Chicago in the first half of the 1900s (described well by Arnold Hirsch in Making the Second Ghetto), white Chicago residents left for the suburbs, encouraged by post-World War II government policies promoting suburbanization as well as racial animus. Such moves transformed numerous Chicago community areas; Englewood, south of the traditional Black Belt, went from 2.2% black in 1940 to 96.4% black in 1970 and North Lawndale, a Jewish population center, transitioned from 0.4% black in 1940 to 91.1% black in 1960.

Amidst these two substantial demographic shifts, what happened to the locations of churches in the Chicago region? I’ve been working on a project that involves mapping church locations in the Chicago metropolitan area at six time points: 1925, 1936, 1948, 1957, 1968-69, and 1988-90. Utilizing address data from directories published by the Church Federation of Greater Chicago, a primarily Mainline Protestant group, I have mapped over 8,500 church locations in a number of denominations (including denominations in the Mainline, Conservative, and Black Protestant traditions).

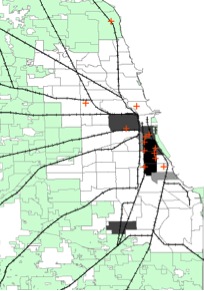

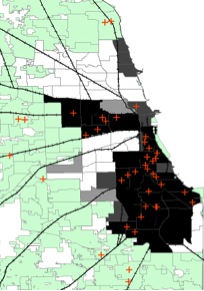

Here are two of the findings thus far. First, not surprisingly, the changing racial demographics of Chicago neighborhoods affected churches. Here are two maps of the locations of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches, first in 1925 and then in 1988-90. The shading on the maps indicates the percent of residents in the community areas who were black: the darkest shade is 40% black or greater while no shading represents 0-9.99% black.

In 1925, twelve of thirteen AME churches in the region were on Chicago’s south or west sides but by 1988-90, eighteen of the forty-nine churches were in the suburbs, mostly in suburban communities with higher black populations like Joliet, Aurora, and Elgin. Concurrently, the number of AME churches in Chicago increased after World War II, primarily in racially transitioning areas such as North Lawndale, East Garfield Park, and Morgan Park. In contrast, DuPage County in 1970 had no AME churches amongst a population of 491,882 - only 1,613 county residents (0.03%) were black. By 1990, DuPage County had 1 AME church and was 1.98% black (15,462 residents).

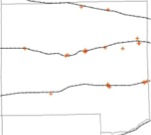

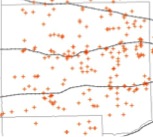

Another aspect of this project involves examining church locations within suburban areas as populations increased with mass suburbanization. I looked specifically at DuPage County, a county with communities first founded in the 1830s and with prominent railroad lines constructed in the mid nineteenth century. See three maps of church locations from 1925, 1968-69, and 1988-90.

In the 1925 directory and amongst the Protestant denominations in this analysis, there were twenty churches in DuPage County (1920 population of 42,120). All were within a short distance of the three major east-west railroad lines or an interurban electric line and are primarily located within older communities/suburbs. As the distance from Chicago grew, the number of churches decreased.

By 1968-69 (population of 491,882 in 1970), there were more churches in more locations including between the railroad lines in new developments and suburbs. The number of churches was still limited in the furthest corners of the county.

Two decades later, development had spread throughout the county (1990 population of 781,666) with churches added in expanding suburbs like Bartlett and Naperville. Development between the railroad lines continued, leading to more churches in the already developed central and eastern portions of the county.

Both of these findings suggest that the locations of churches within a metropolitan region are affected by factors beyond just their congregants or the state of their church buildings. As evidenced here, two influential factors are the movement of different racial and ethnic groups within a region as well as suburban settlement patterns. Protestant churches may have more freedom to pick up and move than Catholic parishes (see John McGreevy’s Parish Boundaries and Gerald Gamm’s Urban Exodus) but where they go may just often depend on social forces beyond their control.